Whilst known and used since the Renaissance, it was the 18th Century that arguably saw the heyday of Pastel painting or crayon painting as it was then known. While some artists still made their own pastels, it was a time-consuming process; during the 18th Century, pastel crayons began to be made commercially to be bought from colourmen, which no doubt helped in its spreading popularity, with a number of artists working mainly in this versatile medium, catering for an ever-increasing demand for portraits that could be executed in a fraction of the time required for an oil portrait.

From the time when the first pastel drawings were made, artists have sought ways to preserve these fugitive, impermanent works, realising that what was essentially coloured dust particles needed to be bound together to prevent them falling from the surface upon which they had been used, but in a way that preserved the initial colouring and effect produced by the artist. There were numerous attempts at different ‘Recipes’ during this time.

Antoine-Joseph Loriot,1 not an artist but an engineer and inventor apparently ‘discovered’ such a method in 1750-53, following a number of experiments and which was presented to the Académie members, but was not then made public. Its existence was announced at the Salon du Louvre of 1763 when the artist Jean Valade exhibited the portrait of Loriot that can be seen below, the accompanying label stating that half of the picture had been fixed with M. Loriot’s ‘secret’ formula, the other half had not been fixed. Although arousing considerable attention at the time, no doubt in large part due to its ‘secrecy’, it was not until the 1780’s that his ‘invention’ was published and made widely available.

In true enlightenment fashion, art and science coming together for the common good.

The following is my translation of one of a number of articles published in the 1780’s, which explained Loriot’s ‘Secret Formula’. The one below appeared in the “Nouvelles de la République des Lettres et des Arts” of 1782, No. XVI, the author being Antoine Renou (1731-1806) painter and playwright, and at the time of the publication, Adjoint de l’Académie Royale de Peinture & Sculpture, which post he held between 1776 and 1790.2

In translating this article, whilst hopefully retaining the spirit of the text to convey what the author intended, I have adapted the text in places to render the reading of it more natural and less awkward than would be the case with certain passages if translated literally.

Secret

The Fixing Of Pastel, Invented By M. Loriot, & Published By The Royal Academy of Painting & Sculpture, In 1780

Renou

The poor adhesion of colours that are used in pastel painting, and the rapid changes they undergo owing to the effects of humidity & moisture in the air, have for a long time led many people to find ways of fixing them. But their efforts were unsuccessful, that is until 1753 when Mr. Loriot, known for many other inventions arrived at his discovery. He informed the Marquis de Menars,3 then Director & Officer-General in charge of the Royal Buildings, who, guided by his taste & love for the Arts, immediately recognised the importance of a way now to keep pieces that had until then had a fugitive and ephemeral existence.

Marquis de Marigny and Marquis de Menars,

Alexandre Roslin, 1763

Chateau de Versailles

He commissioned the Royal Academy of Painting to conduct various tests of this ‘Secret’, which were put before him by, M. Loriot, on October 6, 1753, and the Company conveyed, at its meeting, on the same day, the pleasure they got from it. A little while later Mr. Loriot presented some further examples to the committee to prove that this ‘Secret’ was also effective in eliminating mould stains from paper. This was proved to the members of the Academy of painting by Mr. Loriot ‘fixing’ the reception piece of the famous Rosalba Corriera, who was able in so doing, to render it as almost as fresh looking as when it was first painted.4 After such well-documented successes, the Marquis de Menars granted, by command of the late King, to M. Loriot a pension of thousand livres with the proviso however, that his ‘Secret’ be deposited in a sealed envelope, only to be made public after the death of its Author.

Comte d’Angiviller

Jean-Baptiste Greuze 1763

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Monsieur le Comte d’Angiviller,5 having been appointed by His Majesty as the director of Les Bâtiments du Roi, however, wished that such a useful ‘Secret’ be made public. He conveyed this desire to Mr. Loriot, who, with commendable unselfishness, and thinking more of the public good rather than of personal gain, took this on board. As a result, on 8 January last, M. Loriot went to the Royal Academy of Painting, whom the Comte d’Angiviller had commanded to take note of the process, and in their presence he fixed various paintings and drawings, explaining all the details of the operation as he went, which the Committee was totally satisfied with. It is for this reason that in order to help spread this useful ‘Secret’, they felt they could do no better than to print at their expense, the explanatory paper, containing all the details, as were recorded in the Register.

The Secret :

To successfully fix Pastel, you will need the following,

1: A small ordinary, pocket brush, whose hairs are a little short6

Two examples of French 18th Century clothes brushes, with the hairs on the one to the left perhaps more the length required.

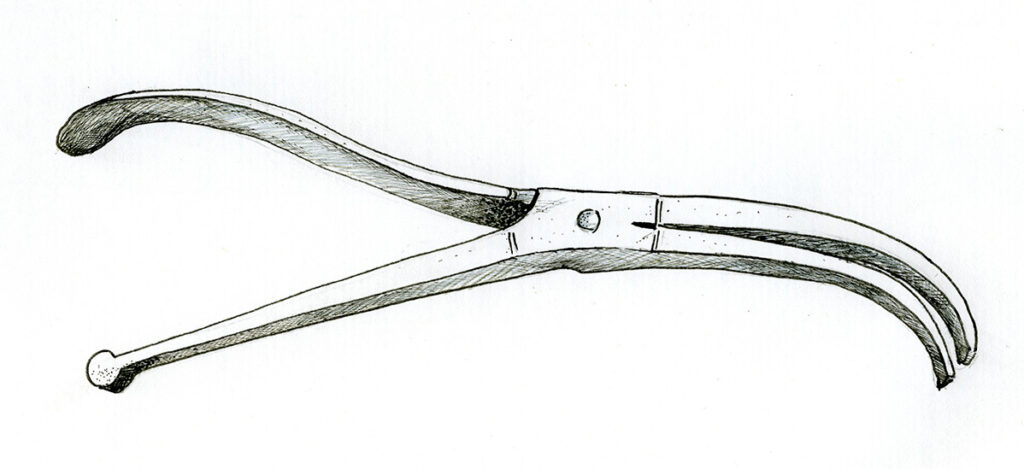

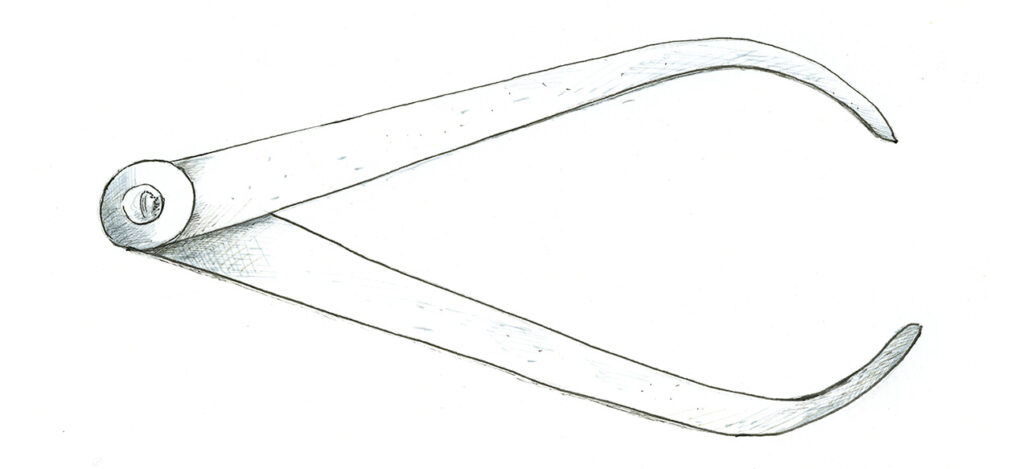

2: An iron rod 6 to 7 pouces long (roughly 12.5 to 14.5 cm),7 either three quarters or triangular in shape, and which is slightly curved at one of the ends similar to a bec de corbin;8 one could substitute this with a tool such as a sculptor’s compass.

Once you have these two objects, it is then a question of preparing the mixture, for which you need a container with about half litre of clean water into which you dissolve about ¼ ounce of fish glue, cut into as many pieces as possible, to speed up the dissolution; bring to the boil in a bain-marie and heat until the fish glue is fully dissolved. Then to ensure that there is no residue, strain through a linen cloth. Then pour a small amount (as much as you will need) of the strained liquid, while it is still hot, into a saucer and then add at least double this amount of best quality wine alcohol (ethyl alcohol). This means that for a tablespoon of glue-water you will need two of alcohol. We should mention here for those you wish to prepare the fish glue in advance that it will easily go off, and to avoid this simply add an eighth part of the ethyl alcohol to the mixture. When you want to use it proceed as outlined above, adding the remaining alcohol. If however, as outlined later, you make the mixture using Kirsch, it will not be necessary as this mixture does not go off.

Once this has all been done, place the pastel painting that is to be fixed, either vertically or lean it at a slight angle on an easel or leaning against the wall, against a chair, a table, etc., then dip the bristles of the brush into the saucer with the mixture, fully soaking them, you will then need to remove most of it so that the bristles only remain slightly wet. You achieve this by passing the curved end of the iron rod, over the bristles, several times, in the same direction, that is, towards you, and not going back and forth.

To begin fixing the pastel, with everything now ready & the brush moistened with the still lukewarm mixture, you will need to hold the brush some 8 to 10 inches from the pastel painting, and pass the curved part of the iron rod over the bristles – you do this by using one of the ends of the iron rod, pulling it constantly towards you in the same direction as before over the bristles, which will result, given the position of the brush an almost imperceptible fine spray, as the rod passes through each bristle; the mixture of wine spirit & glue water, combined over the pastel, will result in it being fixed. You need to repeat the process several times, with the same care, making sure that you go over the whole picture, making sure to keep the brush slightly wet, by dipping the brush in the mixture as it becomes necessary. When the entire surface of the picture has been so wetted, leave to dry thoroughly, and then repeat the process in the same way & in the same manner, a second and even a third time, any more should not be necessary. However there is no danger in doing five or six coats, as this process will not preclude the need to frame the pastel behind glass as normal. The aim in fixing is to ensure that the particles of pastel dust are bound together so that if touched by your fingers the pastel cannot be removed or altered. What would be the point though in doing multiple layers; would we then think that we could rub the surface of the pastel with impunity, but by so doing, would we then not lose the velvety feel of the pastel?

It would also be an error to think that once fixed, the pastel can then be varnished in a similar way, for as much as the mixture detailed above will revive the colours, so a varnish will alter them for the worse.

Instead of using filtered or purified water, you can also dissolve the fish glue in Kervaser (Kirsch), which, in some respects, is more advantageous in that being spirit it dries more quickly; in this case it will be enough with two spoonfuls of the Kervaser and glue mix in the saucer, to add only one spoon of spirits of wine or ethyl alcohol.

We can also by the same process, fix all kinds of drawings. The only difference here being that instead of having the picture vertically or inclined as with the pastels, we can put them flat on a table, as they are not heavily worked; there are however works of very great Masters which cannot be fixed by this method, because of the way in which they have been prepared, either with pumice stone and glue, or the sketch has been previously varnished and subsequently reworked over this layer.

This therefore, as outlined, is the whole process for fixing pastels; its success lies principally in the purity of the liquids used as the basis for the spray, and to their preparation and the correct mixing of the ingredients, which is the result of a number of trials, because if we were to use less water or glue proportionally, the pastel, which is basically a form of dust, would not be sufficiently glued together. If we were to put less spirit of wine and more glue than the amounts recommended, a kind of foam would form on the bristles, which would only deposit large droplets which would leave stains on the pastel; the same would happen if we were to add too much spirit of wine, as this excess would turn the glue, which would thus imperfectly fix the pastel, as, far from depositing a fine spray, the result would rather be large droplets that would not fix the pastel perfectly.

As for the necessary skill for this process, it is essential that you pass the iron rod over the brush without changing direction, always offering up one of the angles of the rod, as it is only by this means that each bristle will be able to release the liquid mixture onto the painting. Thus, because this process means that there is no need to touch the pastel to fix it, it is impossible to alter it, and the spray that covers it, using the precautions listed above, means that it will not change without removing the velvety look of the pastel which is one of its advantages. In addition, all the tests confirm that the colours which are susceptible to being altered by the air, are rejuvenated, and revived by this mixture, added to which, mould stains are removed, as is shown by the certificate of the Academy of December 1, 1753.

In conclusion, we observe that, although having said that it is enough to spray pastels and drawings three times, it is nonetheless better to spray a greater number of layers on charcoal drawings, or those made with soft crayons. If you wanted to limit yourself to only three layers, then you would need to increase the glue in the mixture, and to avoid as result having large drops on the drawings when spraying which would produce stains, you would need to place them vertically or suspended from string as sellers of prints do for display purposes, or by attaching them to card in the same way. There is no need to add that when we limit ourselves to only three layers of spray, it is so as not to lose the surface attractiveness of the pastel, and it is always with the understanding that the pastel will be covered with glass, which will always be necessary to protect against insects, smoke and house dust; but by repeating this process several times, we can render the pastel sufficiently stable so that you can pass your hand over it without risk of removing anything. This degree of fixing may be suitable for drawings or studies in pastel, which one wishes to keep, without putting under glass, to use as originals for students to work from.

Footnotes

- Antoine-Joseph Loriot (1716-1782) French Engineer and Inventor.

- Antoine Renou (1731-1806) Adjoint de l’Académie Royale de Peinture & Sculpture (1776-1790) Then (1790-1793) secrétaire perpétuel de l’Académie and finally secrétaire et surveillant des études de l’Ecole nationale de Peinture until his death.

- Abel-François Poisson de Vandières, marquis de Marigny and marquis de Menars (1727 – 12 May 1781), often referred to simply as marquis de Marigny, was a French nobleman who served as the director general of the King’s Buildings (Surintendant des Bâtiments) between 1751-1773 when he retired. He was the brother of King Louis XV’s influential mistress Madame de Pompadour.

- Rosalba Carriera (12 January 1673– 15 April 1757) was a successful Venetian Rococo painter known for her pastel portraits.

- Charles-Claude Flahaut de la Billaderie, comte d’Angiviller (1730–1809), director of the Bâtiments du Roi (a forerunner of a minister of fine arts in charge of the royal building works) from 1775, under Louis XVI.

- In the original French the word used for this brush is ‘vergette’ which most resembles a modern clothes type brush. Today a decorators wallpaper brush would serve just as well.

- The ‘pouce’, or inch, of the Ancien Régime in France was roughly equivalent to 2.07 cm.

- “bec de corbin” – in English this literally means ‘crow’s beak’. This was the name more generally given to a medieval pole-arm, or hand-held weapon, with a modified hammer’s head and spike on top of a pole, with opposite the hammer head a, pointed spike, curved like the bird’s beak, which was used as the main weapon. However, in the 18th century at the time this was written, it also referred to a medical instrument – a sort of clamp with curved arms used to grasp blood vessels following an amputation, prior to ligating them and this seems the more likely reference here, especially in conjunction with the alternative given of the sculptor’s compass.